-Abraham Lincoln |

|

Digging for Louisiana Roots

Monday Profile

Genealogist sees past in present

By Judy Pennington / Special to the State-Times

TREND Personal Insights

State-Times/ Baton Rouge, La.

1990, Capital City Press

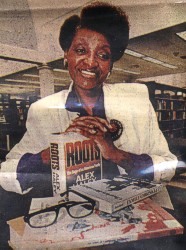

Since childhood, Edna Jordan Smith has felt compelled to find out where people came from and who their ancestors were.

Since childhood, Edna Jordan Smith has felt compelled to find out where people came from and who their ancestors were.

Today, a genealogist, parish reference librarian, speaker and founder of the Afro-Louisiana Historical and Genealogical Society, she's still not certain why the predisposition. But she remembered that as other children played, she followed elderly people around always ready with another question.

Even before adolescence, Smith was fascinated by slavery, largely because of her great-grandmother, who had been a slave. Her great-grandmother, Eliza Page, often told her brother's story.

Around 1850, Narcisse Page had tried to escape to Yankee soldiers but was betrayed by older black slaves and apprehended. Smith's great-grandmother, then a child, never forgot how he was hung by his heels from rafters and how the beatings "whipped the skin off him." Nor did he forget how his owners rubbed salt into the gashes and then threw him in a corn shuck bed.

As she recounted that story, she said without rancor, "That's what was done back then."

But she is closer in time to other events, like the alleged murder of Narcisse Page's grown son decades after the Civil War. In West Baton Rouge Parish - as the story goes - Page's son was accused of impertinence and called from his porch by white men. He was found later, beaten to death, his mouth stuffed with leaves.

When Smith was a child, recounted, her mother was walking home from a baby-sitting job at a white woman's house, nine months pregnant, when LSU football fans, angry about losing a game, threw a sack of pears at Smith's mother. It hit her in the stomach, and a dead, 9-pound baby was born the next morning.

Enraged, Smith's grandmother walked back to the white woman's house and asked why she hadn't driven the pregnant woman home. The white woman told her dismissively, "They were just boys having fun."

As both a genealogist and a descendent of slaves, Smith's memory is long. But her impetus is neither bitterness nor anger - though it could be both and more.

Instead, linking with her past and helping others find their roots yields a sense of belonging and pride in a race that deserves admiration. "There are things that I need to know, and like to know, in order to equate my hardships with those of my ancestors," Smith said.

"That helps me survive. I say to myself that if they went through that, whatever is put on my back today. I'll survive."

As an intensely curious librarian and former public school teacher of Louisiana history, Smith has learned slave migration paths to Baton Rouge, and she can often tell someone's geographic origin by his or her name. Since slaves often took the names of their owners, the plantation of the city from which they were sold, "names like Richmond Virginia Wills tell a story," she said.

But her national reputation comes from her detectivelike penchant for following up interesting bits of information.

In 1979, while casually reading a book, Smith came across a paragraph that mentioned Leon Rene, a 1916 graduate of Southern University who was the first to record Nat King Cole and who penned the songs "Sleepytime Down South," "Rockin' Robin," and "Gloria."

Smith contacted Rene and had him travel to Southern for a homecoming, delivering him from obscurity in Los Angeles, where he was living. He was so grateful that, after he died, his widow sent Smith $1,000 for her Canadian trip - -that's another story.

Contact Us | Homepage