-Abraham Lincoln |

|

Pioneers in Black Education Finally Noted

By Mary Durusau

Magazine Sunday Advocate Feb 16 1986

Five Years of Effort Pays Off

It took her almost five years, but Edna Jordan Smith's dream of having two pioneers in black education recognized has come true. This fall, for the first time, the Louisiana public school history textbook mentions the pair who were instrumental in providing education to blacks in this state from the early 1900's through the 1940's.

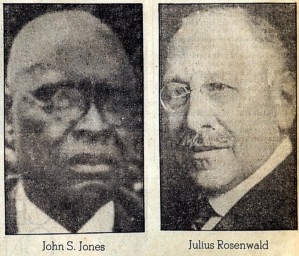

“Long overdue, long overdue” is how Smith describes this recognition for Julius Rosenwald and John Sebastian Jones. Rosenwald, one-time president of Sears Roebuck, donated money for setting up schools for blacks, and Jones was his agent in Louisiana, recruiting people to donate land for schools.

This fall, Our Louisiana Legacy by Henry C. Dethloff and Allen E. Begnaud will include a one-paragraph description of the Rosenwald schools in Louisiana and a picture of Jones, credited to Smith.

A librarian at Westdale Middle School, Smith has been interested in compiling information about black history for some time. “I became interested in it when I realized that there was little or nothing in Louisiana history textbooks, and nothing too much was mentioned about black education and especially nothing about Julius Rosenwald schools when there were 500 of them here in Louisiana.”

In fact, by 1929 Rosenwald had donated money for 372 schools in Louisiana - 28 percent of the state's schools for blacks. In the Baton Rouge area, there were 10 Rosenwald schools, including the Rosenwald Adult Education Center.

While Rosenwald provided money to fund the schools, it was Jones' job to find land for the schools, teachers and the other things needed for a school.

Because the Rosenwald schools “touched so many lives” in this area, there will be a program Thursday at 7:30p.m. at Southern University to mark this recognition for two leaders in black education.

A copy of the book will be presented to Jones' family. Speeches by several local historians will be included, followed by a reception.

“We'd really like to invite the general public, especially people who benefited directly from these schools. So many of us Baton Rougeans, like my father and mother, came from the Felicianas… and the Rosenwald schools really were the only schools in those rural areas,” she said.

Smith also said anyone who has any memorabilia from any of the Rosenwald schools is asked to bring it. At a similar program in May 1980 honoring Jones, a woman brought a report card from a Rosenwald school. That woman's father had donated land for a Rosenwald school in Plaisance, Smith said.

Rosenwald was a philanthropist interested in helping black people. In 1927 he received the William E. Harmon award for Distinguished Achievements in Race Relations. Rosenwald is quoted as saying he was interested in helping blacks. “If we promote better citizenship among the Negroes, not only are they improved, but our entire citizenship is benefited.”

While Rosenwald gave money to other states for schools for blacks, in Louisiana alone he contributed $75, 000 for an adult education program.

But Rosenwald's gifts of money were not simply handouts. There were stipulations about how many days the schools had to be open, because in many areas black children were allowed to attend school only when there weren't crops to be brought in, Smith said.

Jones, who was Southern University's first dean when it was moved from New Orleans to Scotlandville, had the job of finding land on which to build the schools as well as drumming up public support for sending the children there.

“First, he had to impress upon black people the importance of education. So many of them were sharecroppers and used to just getting in the crop, just plantation life, that many of them had grown to feel that it was Utopia or at least as far as they could go. But Mr. Jones was a very knowledgeable man and educated in the classics, and he was chosen as the man to go about and try to start these schools.”

Smith said Jones still was alive when she was a teen-ager, but neither she nor her contemporaries knew the important role he had played in education for blacks in Louisiana. And, ironically Jones' son, Ralph Waldo Emerson Jones, would go on to become a name synonymous with black education as the long-time president of Grambling University.

Now, she wants school children to know some of the history of black education in Louisiana. “Why we're doing this is to educate our young people who are not aware at all of what went on, to keep them abreast of what happened that brought us to where we are today,” Smith said.

Asked why she thinks it took so long to get recognition for the Rosenwald schools in Louisiana textbooks, Smith said, “Well, we inherit things and it's hard to change. You don't find blacks mentioned too much in anybody's books, and you can't blame anybody. You've got to be active yourself.”

Contact Us | Homepage